What happens when the world loses its ability to stabilise disruption

As coordination weakens and recovery slows, disruption now escalates more easily and lingers longer than it once did. The challenge is no longer isolated events, but a world that struggles to stabilise once things begin to move.

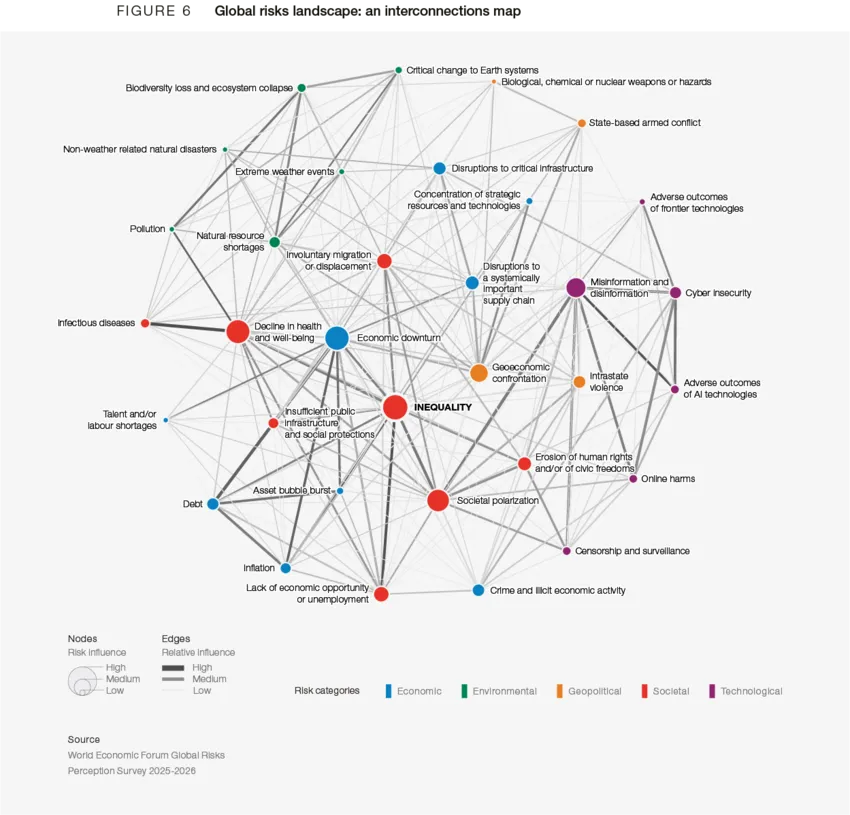

The latest Global Risks Report from the World Economic Forum reflects a shift that many leaders are already grappling with. Supply chain resilience is being tested by weaker coordination and slower recovery across an increasingly fragmented global environment.

The report points to a deterioration in multilateral cooperation and a more contested global order. That matters because, across supply chains and operating networks, disruption now escalates more easily and resolves more slowly than it once did.

This is not because events have suddenly become more extreme. It is because the conditions into which they arrive have changed.

Supply chain resilience used to rely on built-in stabilisation

For a long period, global disruption followed a broadly predictable pattern. Pressure would build in one area, an event would trigger disruption, and a combination of coordination, rules and spare capacity would limit escalation and support recovery.

Trade disputes were mediated through shared frameworks. Transport networks had alternative routes and time buffers. Energy markets were volatile but broadly coordinated. When disruption occurred, responses tended to converge rather than fragment.

This did not eliminate risk. It reduced the likelihood that local disruption would spread uncontrollably or persist indefinitely. Recovery was imperfect, but it could be expected.

That stabilising logic has weakened.

Systemic risk grows as coordination erodes

The Global Risks Report reflects a shift from a largely multilateral world to a more fragmented and competitive one. That shift is not abstract. It translates into thinner coordination between governments, slower collective decision-making and a greater tendency for responses to reflect domestic priorities rather than collaborative outcomes.

At the same time, operational slack has been reduced. Supply chains are more tightly optimised. Labour markets are constrained. Energy systems operate closer to capacity. Decision authority is spread across institutions that do not share incentives or timelines.

Individually, none of this constitutes a crisis. Together, it increases systemic risk by reshaping the environment in which disruption occurs.

Stress reshapes the landscape before any trigger appears

This is where Stress-Trigger-Crisis becomes useful, not as a theory, but as an explanation.

Stresses accumulate in the background. Trade realignment introduces friction. Energy transition adds constraint. Demographic change tightens labour supply. Digital fragmentation complicates coordination. Few of these pressures need to be resolved and most persist.

But, as stresses combine, the system’s tolerance narrows. The distance between routine strain and visible disruption shrinks.

A trigger is still required. That has not changed. What has changed is how much of a trigger is needed to tip conditions into disruption.

Smaller triggers now cause wider disruption

A drought restricts a transport corridor. A tariff adjustment alters routing decisions. A regulatory change slows approvals. A cyber incident disrupts visibility for a few days.

In a less stressed environment, these would likely have been absorbed. Capacity would have been reallocated. Decisions would have aligned. Recovery would have been relatively quick.

In today’s conditions, the same triggers activate multiple pressures at once. Constraints compound rather than offset each other. Escalation travels across logistics, finance, information and politics.

The event itself might be unremarkable, but the consequences are not.

Operational resilience is tested after disruption begins

Once disruption starts, it rarely stays contained.

Physical constraints translate into financial pressure. Information gaps slow coordination and encourage defensive behaviour. Political responses introduce further friction. Reputational concerns narrow options and harden positions.

In the past, stabilising forces worked against this spread. Today, those forces are weaker than the pathways that transmit disruption onward.

This is why disruption now tends to linger. Not because no one wants resolution, but because alignment is harder to achieve and trade-offs are more contested. Operational resilience is no longer about bouncing back quickly, but about limiting escalation and shortening recovery where possible.

Recovery has become the difficult phase

One of the most under-appreciated consequences of weaker stabilisation is what happens after the initial disruption.

Recovery used to benefit from a degree of shared intent and common reference points. Increasingly, recovery paths compete. Measures that stabilise one part of the system may destabilise another. Political, economic and operational objectives pull in different directions.

As a result, disruption does not end cleanly. It fades unevenly, mutates into adjacent problems, or sets the conditions for the next episode.

This is why many leaders feel they are operating in a state of continuous disruption, even when individual events appear manageable on their own.

What this means for managing disruption in practice

If disruption is treated purely as a sequence of events, responses will continue to disappoint.

The more useful question is not what happened, but what conditions allowed a relatively modest trigger to escalate and persist. That shifts attention away from prediction and toward preparation. Away from event severity and toward background stress, coordination capacity and decision processes.

It also explains why simply improving risk awareness is not enough. Awareness has increased. Stabilisation capacity has not.

Implications for leaders

Three implications follow.

First, loss of stabilisation should be treated as a risk in its own right. Leaders should ask where coordination has weakened, where rules are contested and where recovery depends on actors who no longer move together.

Second, internal discussions should distinguish clearly between background stress and trigger events. Many failures originate not in the trigger, but in unrecognised or unresolved stresses: tight capacity, slow escalation, unclear authority.

Third, attention should shift toward how quickly alignment can be restored once disruption begins. Decision speed, pre-agreed thresholds and the ability to act without renegotiating objectives now matter more than comprehensive plans.

The world has not become ungovernable. But it has become harder to bring back under control once it moves. Understanding that shift is now central to building supply chain resilience in a fragmented global economy.

If you want a practical view of how disruption escalates through supply chains and where coordinated action makes the biggest difference, download the How Disruption Escalates guide.

It shows the patterns this article describes and how leaders are starting to design around them.